How to Record a Real Estate Closing Using the HUD Statement

Cash Purchases vs. Loan Purchases (And Why the Journal Entry Matters)

When a home or investment property closes, a large amount of money changes hands in a short period of time. Purchase price, loan proceeds, escrow funding, lender fees, title charges, recording fees, prepaid expenses, and credits are all settled at once. From a bookkeeping perspective, this is one of the most information-dense moments in real estate ownership.

Yet it is also one of the most commonly mishandled.

Many real estate books contain property purchases that were recorded as a single expense, a vague “asset” entry, or a deposit and withdrawal that never fully reconciles. The result is distorted financial statements, loan balances that do not tie out, equity that makes no sense, and confusion when tax season arrives.

The solution is simple but technical: the HUD statement (or Closing Disclosure) must be used to build the journal entry. And that journal entry looks very different depending on whether the property was purchased with cash or financed with a loan.

This article walks through how and why to record real estate closings correctly, using the HUD statement as the source document, and explains the key differences between cash purchases and loan purchases so your books remain accurate, defensible, and tax-ready.

What the HUD Statement Really Is (From an Accounting Perspective)

The HUD-1 Settlement Statement (or its modern equivalent, the Closing Disclosure) is not just real estate paperwork. From an accounting standpoint, it is the authoritative transaction summary of the closing.

It answers four critical bookkeeping questions:

What was acquired?

The property itself, at its total cost basis.How was it funded?

Cash, debt, or a combination of both.What costs were capitalized vs. expensed?

Certain closing costs increase the asset’s basis, while others are immediately deductible or prepaid.Who paid what?

Buyer vs. seller credits, escrows, and adjustments.

Unlike bank statements, which only show cash movement, the HUD shows economic reality. It tells you what actually happened, not just what cleared the bank.

That is why the HUD should always drive the journal entry—not the other way around.

Why Real Estate Closings Require a Journal Entry

Real estate closings almost never fit neatly into a single “expense” or “check” transaction. They involve:

Multiple balance sheet accounts

Asset capitalization

Loan creation

Equity changes

Escrow funding

Prepaid expenses

If you attempt to record a closing using only expense entries, your books will inevitably fall out of balance.

A journal entry is required because a real estate purchase is fundamentally a balance sheet transaction. You are exchanging one set of assets (cash or debt capacity) for another asset (real property), not simply incurring an operating expense.

This is true whether the property is personal, rental, or held by a business entity.

Understanding Cost Basis Before We Compare Cash vs. Loan Purchases

Before diving into the differences, it is important to understand cost basis, because it applies to both purchase types.

Cost basis generally includes:

Purchase price

Title and escrow fees

Recording fees

Legal fees related to acquisition

Certain lender fees (depending on classification)

Transfer taxes (if applicable)

Cost basis does not usually include:

Property taxes paid at closing

Insurance premiums

HOA dues

Interest

Utility prorations

These distinctions matter because basis affects depreciation, gain or loss on sale, and long-term tax reporting. The HUD statement provides the detail needed to make these classifications correctly.

Journal Entry for a Cash Purchase

A cash purchase is structurally simpler, but it is still frequently recorded incorrectly.

What Happens Economically

In a cash purchase:

Cash decreases

Real estate asset increases

No loan is created

Equity remains unchanged (assuming business or investment context)

The buyer is converting one asset (cash) into another asset (property).

Common Mistakes with Cash Purchases

Recording the purchase as an expense

Recording only the purchase price and ignoring closing costs

Posting the entire transaction to a “Real Estate” account without detail

Failing to reconcile escrow withdrawals

Each of these mistakes understates assets and distorts net worth.

Example: Cash Purchase Journal Entry

Assume the following simplified HUD details:

Purchase price: $300,000

Title & escrow fees: $4,000

Recording fees: $1,000

Total cash paid at closing: $305,000

Correct journal entry:

Debit: Real Estate Asset – $305,000

Credit: Cash – $305,000

That is the core entry.

From there, advanced bookkeeping may break the asset into land vs. building, or separate prepaid items, but the essential concept is clear: this is not an expense—it is an asset acquisition.

Journal Entry for a Loan (Financed) Purchase

Loan purchases are more complex because multiple funding sources are involved.

What Happens Economically

In a financed purchase:

A real estate asset is acquired

A liability (loan) is created

Cash may decrease (down payment and closing costs)

Equity may change depending on entity structure

This is no longer a simple asset swap. It is a combination of asset creation, liability recognition, and cash movement.

Key Difference #1: The Loan Is Not Income

One of the most common errors in real estate bookkeeping is treating loan proceeds as income. Loan funds increase cash, but they also create an equal liability. They do not increase profit.

If loan proceeds are misclassified as income, financial reports will be wildly inaccurate and tax filings may be compromised.

Example: Loan Purchase HUD Breakdown

Assume the following:

Purchase price: $400,000

Loan amount: $320,000

Down payment: $80,000

Closing costs paid in cash: $12,000

Total asset cost: $412,000

Correct Journal Entry for a Loan Purchase

The journal entry must reflect three things simultaneously:

The full asset value

The loan liability

The cash contribution

Journal entry:

Debit: Real Estate Asset – $412,000

Credit: Mortgage Payable – $320,000

Credit: Cash – $92,000

This entry mirrors the HUD statement exactly.

Nothing is left “floating.”

Nothing is misclassified.

Everything ties.

Why Cash vs. Loan Purchases Affect Future Reporting

The way a property is recorded at purchase impacts reporting for years to come.

Depreciation

Depreciation is calculated based on cost basis. If closing costs are omitted or misclassified, depreciation will be understated or overstated every year.

Loan Balances

If the original loan balance is recorded incorrectly, mortgage balances will never reconcile to lender statements, even if monthly payments are recorded correctly.

Equity and Net Worth

Misrecorded purchases distort equity, which affects:

Investor reporting

Lending decisions

Business valuation

Exit planning

Tax Preparation

CPAs rely on accurate balance sheets. When property purchases are not recorded correctly, tax preparers are forced to reverse-engineer transactions—often under tight deadlines.

Escrows, Prepaids, and Adjustments: Where People Get Stuck

HUD statements often include:

Prepaid property taxes

Insurance escrows

HOA dues

Seller credits

Utility prorations

These are not part of the property’s cost basis, but they do affect cash and must be recorded correctly.

Depending on the level of bookkeeping sophistication, these items may be:

Expensed

Recorded as prepaid assets

Offset through clearing accounts

The key is consistency and documentation. The HUD tells you exactly what each amount represents.

Why Bank Feeds Alone Are Not Enough

Bank feeds only show:

A withdrawal

A deposit

They do not show:

Loan creation

Asset capitalization

Escrow allocation

Equity impact

This is why real estate closings must not be recorded solely from bank activity. The HUD statement provides the missing context that cash movement alone cannot capture.

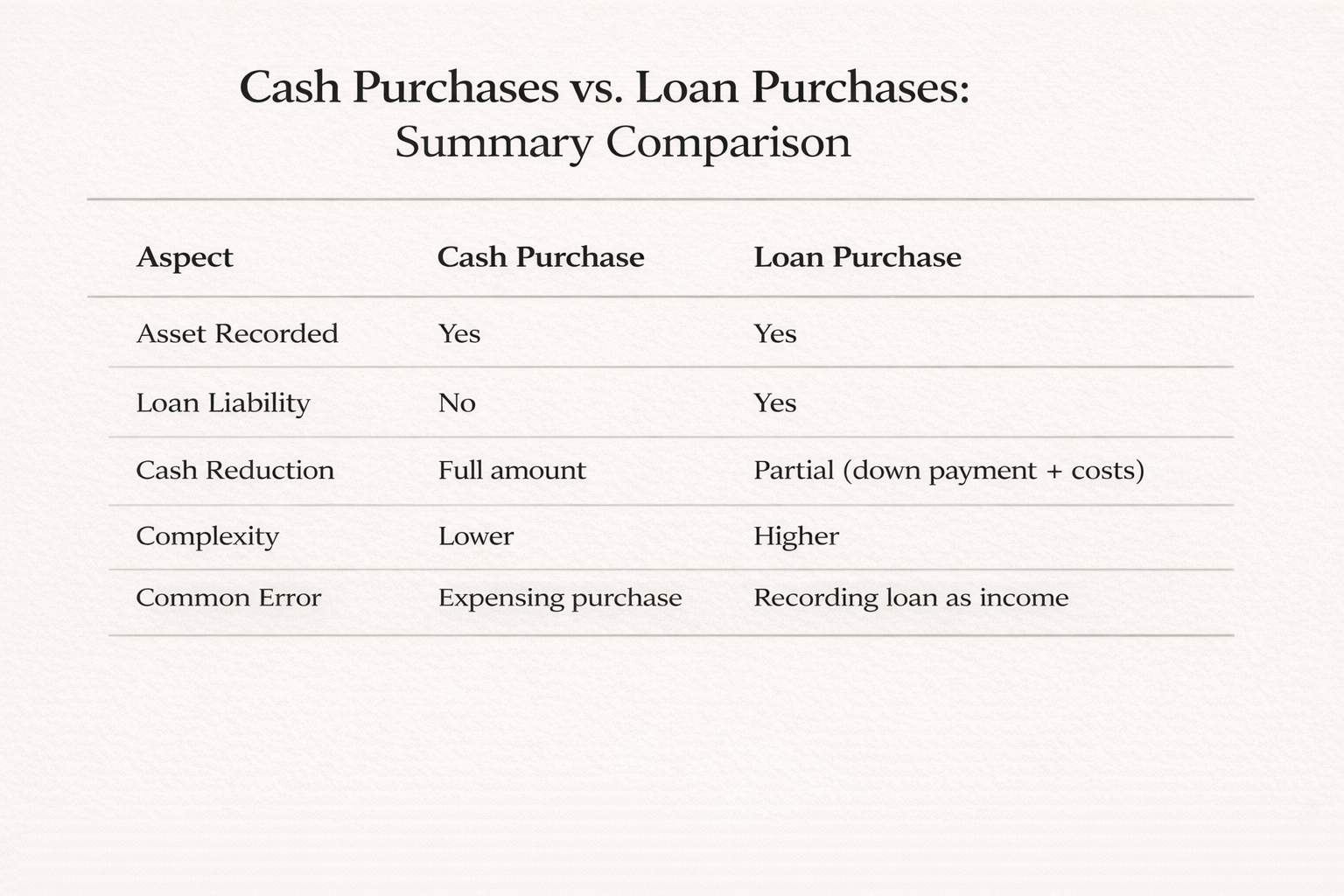

Cash Purchases vs. Loan Purchases: Summary Comparison

Both require journal entries. One simply has fewer moving parts.

Why This Matters for Investors, Business Owners, and Professionals

Clean books are not just about compliance. They are about decision-making.

When real estate purchases are recorded correctly:

Financial statements reflect reality

Loan balances tie to lenders

CPA handoffs are smooth

Tax filings are defensible

Investors and banks trust the numbers

When they are not, every report downstream is compromised.

Final Thoughts: Start at Closing, Not at Tax Time

Most real estate bookkeeping problems begin at closing and surface months or years later. By the time tax season arrives, the damage is already done.

The HUD statement is your roadmap. Whether the purchase is cash or financed, the correct journal entry ensures the property is recorded accurately from day one.

If you are unsure whether your past closings were recorded correctly, reviewing the HUD statements and rebuilding the journal entries is one of the highest-impact cleanup steps you can take.

Clean real estate books start at closing—and everything else flows from there.